Sometimes people wonder whether programming languages should be called languages at all. After all, fundamentally they are quite different.

A programming language is essentially a set of instructions on what to do, and how to do it. The “listener” (the computer) follows the instructions exactly the way they are laid out, with results that are often just as hilarious as they are tragic. There is no back and forth between you and the computer using the same language, just your instructions and then a result that hopefully matches what you intended to happen. Fortunately, your “listener” is infinitely patient, and you have the chance to rewrite your instructions over and over until the result matches what you hoped to see.

A natural language is also used to achieve some desired goal, but in a much different and often more roundabout manner. “Let’s get a cup of coffee sometime” does not mean “let’s drink two beverages together and return to our previous state once they are consumed.” It means “I want to get to know you better…” or maybe even “I don’t want to get to know you better” when used by someone who is trying to quickly end a conversation! Natural languages live in the moment. They involve more muscle memory and context, culture, and even mood. You don’t have an unlimited number of tries to get your point across either, generally only about two or three before your listener runs out of patience. But the roundabout nature of natural languages has an upside too, because 100% precision and correctness isn’t necessary. Saying “That there book…please… give you me, okay?” gets the point across just as well as “Could you hand me that book?” Even just grunting and making an impatient gesture towards the book can sometimes be enough for the listener to understand and hand it to you.

Nevertheless, both natural and programming languages are used to achieve a common goal: being understood in order to get something done. Both are simply methods of bending reality to your own will a little bit by trying to get someone else, or something else, to do what you want them to do.

Meanwhile, others around you are also using their natural languages and their programming languages to try to achieve their own goals, and there are many more of them than there are of you. And because of that, both types of languages are used for the most part in the same way: passively. This is why people spend more time reading than writing and more time listening than speaking, and developers spend a lot more time reading external code than they do writing their own. So the two are quite similar in this respect: you want a good passive understanding of what is around you, with the ability to actively form your own phrases to get the results that you expect.

These similarities are fortunate, because they allow you to port learning techniques used for one to the other. My own experience learning both has shown the same. While I personally took to programming at a young age, I then put it off entirely and spent the next few decades with natural languages. (It wasn’t until much later that I properly learned to code, and thanks to Rust no less!) Natural languages began with Japanese and a move to Japan not long after high school, then to Korean which took me to Korea where I live now, and soon turned into a lifelong addiction with a large collection of languages at varying degrees of proficiency. The desire to know more and more languages led to experimentation with a lot of learning methods, but they all had one thing in common: they involved a ton of passive input with interesting content created by native speakers.

On the natural language side this meant doing things like reading the whole set of Urusei Yatsura ( a fantastic Japanese manga from the 1980s), and for Rust it was only after watching a user named Brookzerker go through the Rust Book page by page that the language started to click. (Live coding being the programming language equivalent of native speaker content for natural languages)

Finding just the right content for you takes time, however, and is only enjoyable if you are motivated. Is there a method that distills this approach into a single piece of content so that new learners don’t have to search through tons of content to put it together themselves? Indeed there is, and it’s pretty close to perfect.

The idea of making the perfect learning method is a most attractive one. If it’s possible to put together a textbook that is as dry as dust to the point that even the most enthusiastic learner can’t make use of it, then its mirror opposite should be possible too: the perfect book. Such a book would completely absorb the reader, who is then incapable of putting it down, ends up reading the whole thing, and comes out the other side knowledgeable and excited to learn more. Well, a book that is so enrapturing that it can’t be put down is certainly more theory than reality, but it turns out that natural languages have a technique that is pretty close to ideal, and it comes from an idea known as “comprehensible input.”

Comprehensible input: the learning sweet spot

Comprehensible input is most famously laid out by linguist Stephen Krashen in a hypothesis on language learning which treats it as one of the most effective ways to learn a language. Comprehensible input should ideally should be a consistent flow of what is called “i+1”. “i” refers to the learner’s current level, while “+1” is the next level: language that is “just beyond” the reader’s current level of competence. When putting a textbook together, maintaining this i+1 throughout is key.

Anything else is less than ideal. Interacting with content at or below your level gets boring quickly, while content far beyond what you are comfortable with just doesn’t click and can be frustrating.

The language learning method that best encapsulates this is called the “natural method” or the “direct method.” It involves simply diving into the target language. But how do you do that when you are an absolute beginner? The answer is surprisingly simple: even just a few words is enough to start forming understandable sentences. You then repeat them in varied forms, adding new words slowly, and before you know it you find yourself understanding a new language. Meanwhile, readers who already know the basics of a language can simply skim the first few chapters until the level of the material reaches their current level and make that the starting point.

You can see this method in action in a number of existing books. One popular series of books from the mid-20th century by the Nature Method Institute taught English, Italian, French, and many other languages. Their English By The Nature Method book shows just how simple the sentences in the first chapter are:

Mr. Smith is a man. Mrs. Smith is a woman. John is a boy. Helen is a girl. The baby is also a girl. Helen and the baby are girls…

By the end of the first chapter, the language has already become a bit more complex, simply by gradually adding new words and concepts in context:

The three (3) children are the son, the daughter, and the baby daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Smith. The father, the mother, the son, the daughter, and the baby daughter are a family of five (5) persons.

So far, so good! As the author of such a book, now your task is to keep the reader around for the full length of the book. For that you need a story. After all, nobody is going to stick around for hundreds of pages just to encounter more and more complex ways to talk about the members of a family.

Story is exactly what these books deliver. Let’s skip forward five chapters, by which point the reader has already been exposed to a full 30 pages of the target language:

Are trees the only plants in the garden? No, there are also other plants in the garden. Is Helen the only girl in the family?

Still quite simple, but not bad. Let’s skip ahead another five chapters:

This morning John asked his father, “Father, when will you take us to the lake?” “I shall take you there today,” his father answered. “Will you come with us, George?” he asked his brother.

By reading this content that is easy to understand yet just new enough to be interesting, near the end of the book the reader has naturally come to understand content like this:

I wonder if you can help me to come to a decision,” he continued, pulling a small object out of his pocket. When Storm showed it to him, Marshall saw that it was a very small book of songs, in fine leather with gold letters printed on the back.

That’s the method in a nutshell. It’s simple and effective, and it feels almost magical. Of the books I’ve read that use the method, my two favourites are L’italiano Secondo Il Metodo Natura for Italian, and Lingua Latina per se Illustrata for Latin, precisely because of their stories. Both of them do a fantastic job introducing the language and region in question, but they aren’t just bland expositions. The Italian book has Bruno, a young man who introduces a lot of Italian history and culture, and who would have been in danger of being a bland character were it not for the fact that for some reason he keeps on just barely cheating death throughout the book: is hit by a car,

almost drowns in the ocean,

falls off a cliff,

you name it. Others include Bruno wandering with his friends in the woods facing possible death by freezing and starvation, Bruno alone in the dark with bottles trying to find a gas station to fill them up to bring back to the car, Bruno and his friends evading a car chasing them from behind…

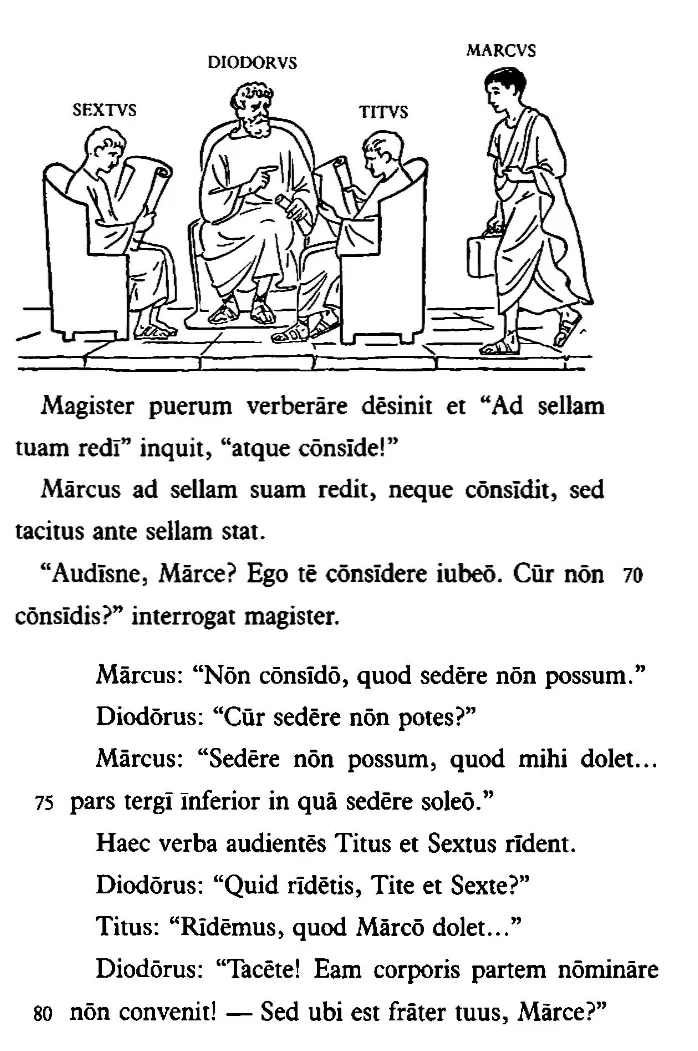

Meanwhile the Latin book has a fan favorite named Marcus, who is a bit of a Calvin: his grades at school are right at the bottom, but he also has the quickest wit and is clearly bored with the whole thing.

You can tell that the authors had a great time writing these books, and the stories are unique enough that you find yourself reading all the way to the end just to find out how they end.

Interestingly, this simple yet magical method is also tiring in the same way that physical exercise is tiring. This seems counterintuitive, but then again, a marathon is simply putting one foot in front of the other, and swimming 50 laps is simply pushing yourself forward in the water over and over again, but those are still tiring. It’s the repetition over a long period of time that leads to growth, and the natural method books have repetition in spades because they are long. (The one for French clocks it at over 1,100 pages!) You can’t have immersion if there isn’t enough content to immerse you for a long period of time. This length is key, because you don’t want a reader who has finished one of these books to decipher the target language anymore. Instead, they should immediately recognize words and phrases without effort because they have already appeared so many times in the book.

I followed the idea of comprehensible input in two books that I put together, one for a language called Occidental, and the next year for a book called Easy Rust that I wrote not long after learning Rust to try to make the experience easier for someone completely new to programming. Both of them use this approach, with the Occidental book being somewhat more faithful to the method as it also has a background story in the same way that the Natural Language books do. Although this time it wasn’t my own story: I translated Bram Stoker’s Dracula into the language over the space of 100 chapters, starting with the simplest language possible.

(That’s one tip for anyone wanting to try this method out: you don’t necessarily have to come up with your own story! You can rewrite or borrow an existing one.)

This is when EdgeDB and I finally got together. EdgeDB is both type safe and extremely expressive, and the query language is quite easy to pick up. But “easy to pick up” still means sitting down for a while and getting used to how it works. As a new database, EdgeDB needed to have a way to convince people to drop what they are doing, sit down, and give the query language some time to allow it to gel. Interacting with the query language in a natural and fun way is the easiest way to not just hear about, but to get a feel for the advantages it brings.

This point is crucial, because when developing a new product there are two challenges. The first challenge is fairly simple: the world is still unaware of what you have made, so you have to start telling people about it. This is when the second challenge begins, which is a more subtle one. At this point there is a danger that what you have put together to introduce your product only captures the audience’s attention for a minute or two. The danger here is that people might end up thinking they know what it is, actually don’t, and don’t take the time to properly give it a try.

A quick movie analogy here might help. Take The Truman Show, one of the best movies of all time. What are the ways you could introduce the movie to your friends so that they feel the same? Your friends are probably in one of the two following groups:

-

They haven’t heard about it at all. That’s fine, because they are ready to hear about it from you.

-

They’ve heard the name before and maybe that it’s good. This is even better, because they are anticipating a first impression of the movie but have a mind that is receptive to what it might be. They are ready to view the movie without any preconceptions except that it will probably be good.

Moving from this stage to “knowing” it is the risky part. Your friends might do the following, which is good:

-

They watch the movie and absolutely love it. Task complete! They gave the movie their full attention, and now both understand and love it.

or they might alternatively do the following, which is bad:

-

They read a few spoiler-filled reviews about it, or the movie comes on while they are talking amongst themselves and fiddling around with their phones. They end up “knowing” the movie as “the one about the guy that’s in a show or something” but never really felt it. Worse, that sensation of already knowing it makes them less likely to give it a second look. (This, by the way, is why people that want you to check out a movie they really like are so ardent that you give it your full attention.)

The same applies to something like a database, where first impressions are critical. Ideally you want someone to not only know, but also have a feel for what it is. A quick overview of the features and the query language’s syntax might do the trick, but it might fail to capture its spirit.

The way to counteract this risk is to put together a single source that outright immerses and entertains a reader for a good length of time — the longer the better. This is what Easy EdgeDB was created to fulfill, and it follows the steps of the natural method books listed above. Fortunately, the book Dracula turned out to be a perfect fit for this book as well. Not only is it still an entertaining read after over 125 years, but the book itself is written in a so-called epistulary format: a collection of letters and other writings from the characters, complete with dates and locations. You can see this style right from the first paragraph:

3 May. Bistritz.—Left Munich at 8:35 P. M., on 1st May, arriving at Vienna early next morning; should have arrived at 6:46, but train was an hour late. Buda-Pesth seems a wonderful place, from the glimpse which I got of it from the train and the little I could walk through the streets. I feared to go very far from the station, as we had arrived late and would start as near the correct time as possible. The impression I had was that we were leaving the West and entering the East; the most western of splendid bridges over the Danube, which is here of noble width and depth, took us among the traditions of Turkish rule.

That’s perfect for a database! Right away we are dealing with dates, locations, characters and events. And the vivid settings in the book made it easy to come up with illustrations that fit the mood. In our case, we modified them a bit to give them a steampunk feel to add a techy vibe to the original setting.

Easy EdgeDB imagines that we are taking the first steps to create a fantasy game based on the setting in the book, and are just beginning to put our schema together as we encounter EdgeDB for the first time.

In practical terms that means lots of migrations, starting from the absolute simplest schema as we continue to hammer away at it and make improvements.

Following the natural method, the first examples in the chapter couldn’t be simpler. The book starts with an empty type called NPC:

type NPC;We then give the NPC a name and a list of places visited, because our first NPC named Jonathan Harker (the poor fellow who visits Dracula unaware of what a monster he truly is) mentions a few locations that would be nice to put into a database. We start with strings for both Jonathan’s name and the places that he has visited:

type NPC {

required name: str;

places_visited: array<str>;

}With this schema in place, we insert our first object, the NPC named

Jonathan Harker.

insert NPC {

name := 'Jonathan Harker',

places_visited := ["Bistritz", "Munich", "Buda-Pesth"],

};Next, we put together a City type:

type City {

required name: str;

modern_name: str;

}Then insert some City objects:

insert City { name := 'Munich' };

insert City {

name := 'Buda-Pesth',

modern_name := 'Budapest'

};

insert City {

name := 'Bistritz',

modern_name := 'Bistrița'

};At this point we have naturally worked into the concept of links, because

we have a problem: Jonathan Harker isn’t linked to anything! He is an NPC

object that holds the names of a few cities, but there is nothing connecting

him to the existing City objects in the database. Time for a schema

migration! Schema migrations are a breeze in EdgeDB, which is why they

are so common in the book.

type NPC {

required name: str;

multi places_visited: City; # This is now a link to City objects

}In no time at all, the reader of Easy EdgeDB is already used to EdgeDB’s strict types, schema migrations, and links just by traveling with Jonathan Harker and all the rest of the characters through their harrowing adventure. The database schema gets more and more complex as we try to put something together that might be a good for a game based on the story.

You can see this increased complexity just five chapters later in the same

NPC type, which now looks like this:

scalar type HumanAge extending int16 {

constraint max_value(120);

}

abstract type Person {

required name: str;

multi places_visited: Place;

lover: Person;

property is_single := not exists .lover;

}

type NPC extending Person {

age: HumanAge;

}But to the reader it doesn’t look complex at all, because over the past four chapters we have iterated over the existing types so many times over so many migrations that it feels like the reader’s own project. The fun of following the story is what pulls you through the 74,000 or so words that the book contains (a length just shy of the first novel in the Harry Potter series). Of course, many readers will stop halfway and begin building their own EdgeDB projects, which is precisely the point — just in the same way that you can stop reading Français par la méthode nature to go fly to France and start trying out what you know. For these books, length is key. It’s a long immersive experience that you can follow all the way to the end, or stop midway and pick up again later if you feel like it.

It’s thanks to these books that when I see a word like iubeō or prāvē

I think of the poor teacher Diodorus trying to get Marcus to pay attention

to his studies, as opposed to a dry vocabulary card saying that iubeō means

I order (you to do something) or that prāvē means incorrect. Similarly,

readers who finish Easy EdgeDB will see constraint max_value() and

remember how it was used to constrain humans to a certain maximum age

(as opposed to vampires who don’t have it), or see a page on EdgeDB’s

sequence type and remember how it was used to keep track of the player

characters in the imaginary game around which the book is based.

The future

Easy EdgeDB has also gone through some changes since it was first put together, most recently with a fairly large expansion in 2023 to match the changes in EdgeDB 2.0 and 3.0, which were possibly EdgeDB’s largest releases. EdgeDB is now approaching feature maturity with new releases now taking place every four months, making the set of features added to EdgeDB 4.0 during the joint EdgeDB 4.0 / EdgeDB Cloud release smaller than the previous two versions. Aaccordingly, future changes to Easy EdgeDB will probably also be more gradual than the 2023 expansion.

Nevertheless, there are some upcoming changes that are planned:

-

An interactive database allowing the reader to interact with the schema and objects per chapter without having to install EdgeDB, in the same way that our tutorial does.

-

More artwork. The first few chapters of the book are beautifully decorated but thereafter the images drop off. Having images throughout the book will make the experience even more immersive.

-

Changing the existing content to add newer features that fit better than existing implementations. For example, one part of the book imagines a type used to keep track of ship visits to ports so that any player characters visiting a city will be able to see any ships docked at that point in time. EdgeDB 4.0 added a type called

multirangethat might help here: a ship could visit a location over amultirangeoflocal_dateto allow a single property to encompass a single ship’s entire length of visits. -

Maybe your ideas for the book? If you have any requests to make the experience even better, let us know on our community Discord!